SDLC Life Cycle Models Explained: The Surprising Frameworks Teams Overlook

If you've been on even a few software projects, you've probably heard the phrase software development life cycle a dozen times. However, if someone says SDLC life cycle models, people directly think of Waterfall or Agile. I mean, they are significant, but they are not everything. From my experience, teams that choose the correct model for the issue and situation end up quicker, with fewer surprises, and deliver better products. This post walks through the main types of SDLC models and highlights some lesser-known but practical frameworks teams often overlook.

I'm writing this for software developers, project managers, and tech students who want a clearer mental map of software development frameworks. Expect practical advice, quick examples, and common pitfalls. No fluff. If you want to skip to next steps, there's a helpful links section at the end.

Why models matter

Before we jump into the models, let's clarify why choosing an SDLC model matters. The model shapes how you plan, how you estimate, and how teams communicate. It influences risk, testing schedules, stakeholder involvement, and even which tools you pick. Pick wrong and you'll fight misaligned expectations for months. Pick right and the team hums.

Think about it like building a house. If you know the plan, you pour the foundation once. If the plan keeps changing, you want modular components that are easy to swap. Same idea with software. The model you choose answers questions like: How often will we deliver? How much upfront design do we need? How will we handle change?

How I like to pick a model

Here's a simple checklist I use when deciding which SDLC model to try first:

- How clear are the requirements? If they're vague, favor flexible models.

- How risky is the domain? High-risk systems need frequent validation and strict testing.

- How fast do stakeholders want features? Rapid delivery favors iterative approaches.

- Do we need regulatory compliance or heavy documentation? That pushes toward more formal models.

- How experienced is the team with the domain and tech? Less experience suggests shorter feedback loops.

Answering those five questions usually points me to a shortlist of models to try. Below I explain the models and the trade offs.

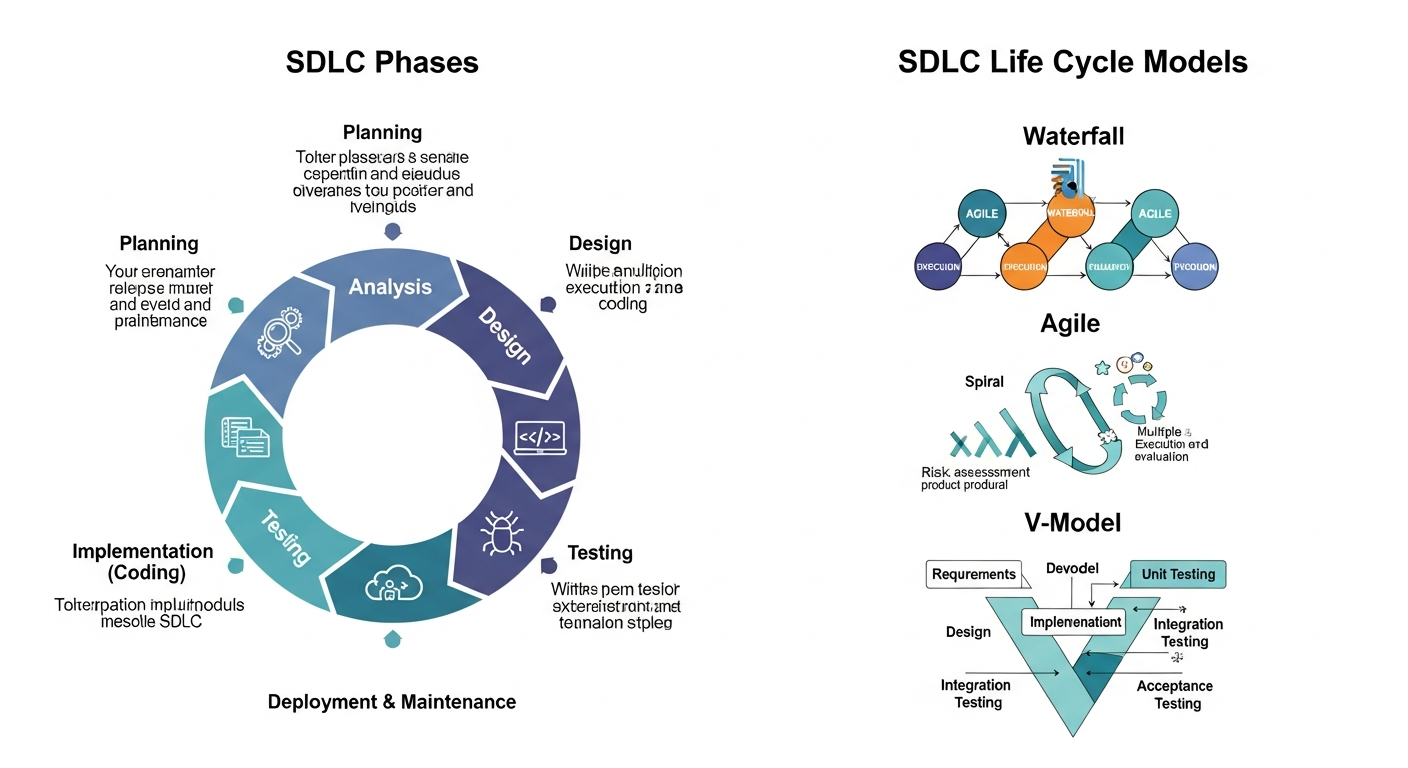

Classic models: Waterfall and V-Model

These are the first things many people learn in class. They are simple to understand and still useful in certain contexts.

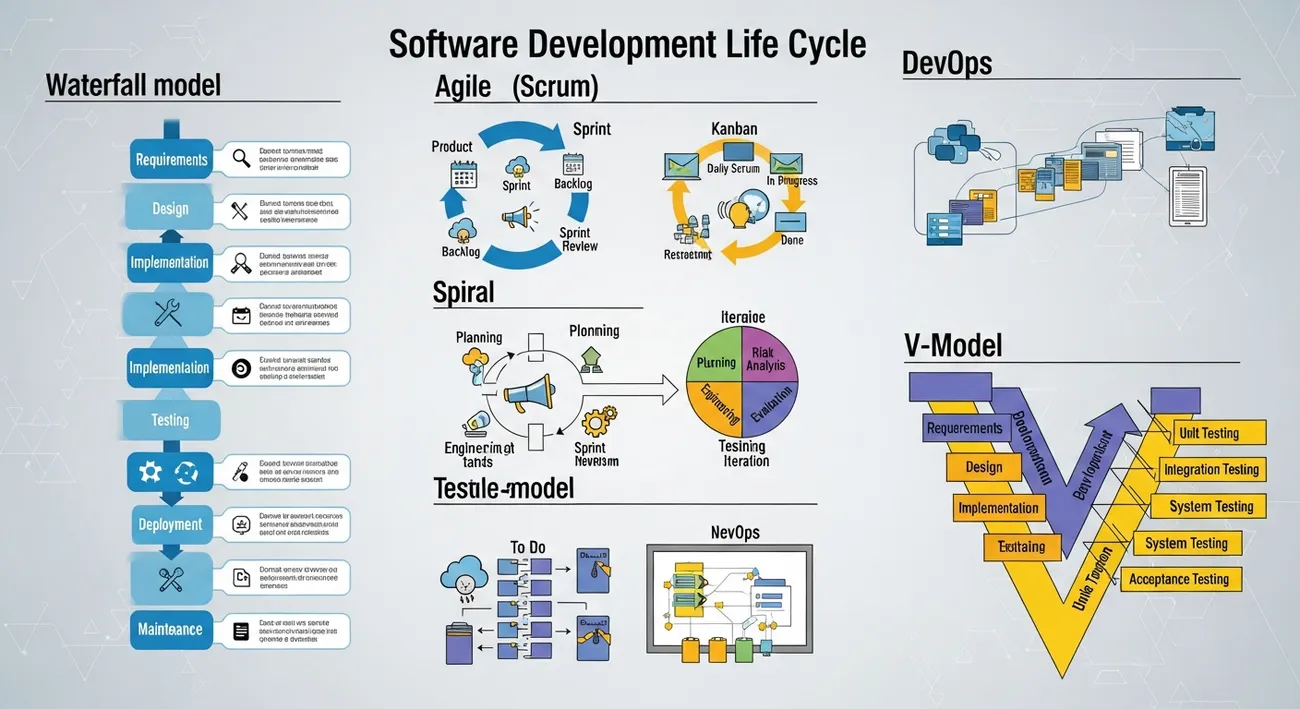

Waterfall

Waterfall is a linear sequence: requirements, design, implementation, testing, deployment, maintenance. You finish one stage before starting the next. It sounds neat and predictable. Early on I worked on a project for a client who insisted on Waterfall because of contract clauses. It was painful when requirements changed, but the documentation was great for audits.

When to use it

- Requirements are stable and well understood.

- Regulatory or contractual needs require heavy documentation.

- Teams prefer a plan-driven approach.

Common pitfalls

- Late discovery of wrong assumptions. You only test near the end.

- Change resistance. Small changes become expensive.

- Poor stakeholder feedback during development.

V-Model

Think of the V-Model as a Waterfall with testing built into every phase. Each development stage has a corresponding test phase. You plan tests early, which catches issues sooner.

When to use it

- Safety-critical systems where testing and traceability are vital.

- Projects requiring formal verification and validation.

Common pitfalls

- Still heavy on upfront planning.

- Can be slow to adapt to changing requirements.

Iterative and incremental models

These models break work into smaller chunks. That reduces risk and delivers value faster. In practice, they can be a better fit than trying to predict everything up front.

Iterative model

In iterative development you build a version, get feedback, then refine. Each cycle improves the product. It's useful when requirements are evolving or stakeholders want to see progress often.

Example: launch a basic reporting feature in two sprints, measure usage, then expand it based on feedback. That beats guessing which metrics people actually care about.

When to use it

- Requirements will evolve or aren't fully known.

- You want regular feedback to refine direction.

Common pitfalls

- Risk of accumulating technical debt if refactoring is neglected.

- Scope creep if iterations lack clear goals.

Incremental model

The incremental model delivers the system in parts. Each increment adds functionality that integrates with previous ones. You get usable software early, not just demos.

Example: build user authentication in the first increment, then add account management, then billing. Each increment ships and is usable.

When to use it

- When delivering early value is important.

- When the system can be built as a set of independent features.

Common pitfalls

- Architecture must support incremental integration. If not, later work becomes expensive.

- Poor prioritization of increments results in less business value to be gained early on

- Agile family: Scrum, Kanban, and hybrids Agile is a set of principles and practices that are under one umbrella. Teams use the Agile framework to be more adaptable, get faster feedback, and deliver continuously. Scrum and Kanban are two of the most widely recognized "flavors" of Agile.Each fits different team constraints.

Scrum

Scrum structures work into fixed-length sprints, usually two weeks. You have roles like Product Owner, Scrum Master, and a cross-functional team. Planning, daily standups, reviews, and retrospectives are core rituals.

Why teams like it

- Delivery in a somewhat predictable manner.

- The main focus clearly being the prioritized backlog.

- There are always some built-in possibilities for continuous improvement.

- On a practical note: Scrum is most effective when the team is able to commit to the sprint goals. If your stakeholders keep insisting on a continuous stream of ad-hoc changes, then implementing Scrum in its pure form will be rather frustrating.

Kanban

Kanban focuses on flow. Work items move through columns on a board. There are no fixed-length sprints. You limit work in progress to reduce context switching and increase throughput.

Why teams like it

- Flexible and less interrupting to the continuation of support work. Perfect for maintenance teams and operations-heavy environments.

- Practical point of view: I have been recommending Kanban quite frequently when teams feature work and production support have to be balanced simultaneously. It is easier to implement than Scrum.

- Most of the teams don’t operate with pure Scrum or pure Kanban. They blend elements to suit their circumstances. For instance, a team might decide to retain Scrum sprints but utilize a Kanban board for troubleshooting. Mix and match, but keep the intention transparent.

- Risk as the main focus: Choose models that allow for frequent validation and prototyping if risk is the primary concern.

Spiral model

The Spiral model combines iterative development with systematic risk analysis at each loop. You prototype, analyze risk, plan the next cycle, and refine. It's heavy on planning and risk assessment, but that's intentional.

When to use it

- Projects with high technical or business risk.

- New products or unproven tech stacks.

Common pitfalls

- Can be bureaucratic if risk analysis is overblown.

- Needs experienced leads to identify real risks versus noise.

Prototype model

Prototyping means building throwaway or evolutionary prototypes to validate ideas. I recommend prototypes when stakeholders can't articulate their needs or when usability is uncertain.

Example: build a clickable UI prototype for a mobile app, test with users, then turn validated parts into real components.

Common pitfalls

- Mistaking a throwaway prototype for production code.

- Delaying architectural thinking until too late.

Rapid models: RAD and Lean

When time to market is your top concern, consider rapid models that favor speed and iteration.

Rapid Application Development (RAD)

RAD emphasizes quick prototyping, user feedback, and short development cycles. You often use visual tools, low-code platforms, or skeleton apps to prove concepts fast.

When to use it

- Short deadlines and flexible scope.

- Projects where user feedback drives the shape of the product.

Common pitfalls

- Risk of messy code if quality gates are skipped.

- Scaling a RAD-built system can be hard without an architecture plan.

Lean software development

Lean, a concept initially borrowed from manufacturing, concentrates on getting rid of waste, providing only what is necessary, and making the entire flow as efficient as possible. The area of use shifts with Agile, but Lean is more strictly oriented towards efficiency.

Handy tip: If you Lean-ize your work without actually implementing Lean formally, the team will still manage to get rid of unnecessary meetings and make the approval process more straightforward.

DevOps is not really a Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) model. It represents a culture and a set of practices that integrate development and operations. However, since it significantly changes the way software is developed and delivered, we decided to include it here.

What DevOps adds

- Automation for build, test, and deployment pipelines.

- Shorter release cycles and faster feedback from production.

- Shared responsibility for reliability between developers and operators.

When DevOps makes sense

- You need frequent releases and real-time monitoring.

- You want to reduce friction between teams responsible for code and for running it.

Practical note: I always push for at least basic DevOps hygiene. Automate builds and tests early. It saves debugging hours later.

Choosing the right model: practical heuristics

Try this decision rubric when you need to pick one of the types of SDLC models. It's not a law, just a quick way to narrow choices:

- If requirements are stable and compliance is strict, consider Waterfall or V-Model.

- If requirements are fuzzy and you need early feedback, go iterative or prototype.

- If speed and adaptability matter, choose Agile, Scrum, or Kanban.

- If risk is high, use Spiral or mix risk analysis into iterative cycles.

- If you ship often and need reliability, invest in DevOps and continuous delivery.

One more rule of thumb: start with the simplest model that covers your biggest risks. Simple beats fancy when things are uncertain.

Common mistakes teams make

I've seen similar failure patterns across teams. Here are the ones to watch out for:

- Picking a model because it sounds modern rather than because it matches constraints.

- Mixing practices without a purpose. Rituals should solve a real problem.

- Ignoring architecture when using rapid or incremental approaches. Short-term speed can cause long-term pain.

- Failing to update the model as the project context changes. Models are not contracts.

- Neglecting testing until late. Continuous testing reduces surprises.

If you only fix two things today, make them: test earlier and improve your feedback loops.

Real world examples — short and practical

Here are three quick scenarios and models that worked well.

-

Internal admin dashboard for a small company.

Simpler requirements, frequent small changes. We used Kanban. The board kept priorities clear and handled support tasks without disrupting feature work.

-

Healthcare device software with compliance requirements.

We used V-Model combined with rigorous traceability and automated testing. It slowed development but made audits less painful.

-

New mobile startup product with an unknown market fit.

We started with rapid prototypes, validated with users, then moved into Scrum for disciplined feature delivery. That avoided building features users did not want.

How to transition models without chaos

Switching models mid-project happens. Here are steps I recommend so the transition doesn't break the team.

- Discuss why the change is needed and what problem it solves.

- Map existing artifacts to the new model. For example, convert a Waterfall requirements doc into a prioritized product backlog.

- Introduce new rituals gradually. Add a retrospective before changing ceremonies.

- Keep an experiment mindset. Try the new model for a few sprints or cycles, then review.

- Train people on roles and expectations. Role confusion kills adoption.

Small experiments reduce resistance. If the team sees wins quickly, adoption follows.

Measuring success: metrics that actually help

Metric overload is real. Don't track everything. Here are a handful that give meaningful signals across models.

- Lead time. How long from idea to running code in production?

- Cycle time. How long to finish a work item?

- Deployment frequency. How often do you release?

- Change failure rate. How often do releases cause problems?

- Customer satisfaction or NPS for the product area.

- Identify a handful of them, continuously measure, and rely them on to improvements. Metrics are means, not ends to be gamed.

- Architecture and quality: not without them One might be tempted to merely focus on feature by feature and to overlook the architecture when the time for deliver is short. That rarely pays off.

- Good architecture enables incremental models to scale. It also saves time during integration.

Some practical tips

- Design for change. Identify likely change points and buffer them with APIs or modular boundaries.

- Automate tests, linting, and security checks. Make them part of the pipeline.

- Refactor often. Short refactors are less risky than one big rewrite.

One small example: adding a clean public API layer might take two extra days early on, but it saves weeks when integrating multiple teams later. I learned that the hard way.

Tools and practices that support models

Different SDLC lifecycle models pair well with different tools. Here are practical pairings I use.

- Scrum: backlog tools such as Jira, Sprint boards, definition of done templates.

- Kanban: simple boards like Trello or Azure Boards, WIP limits, cumulative flow diagrams.

- DevOps and continuous delivery: CI/CD tools like Jenkins, GitHub Actions, or GitLab CI, in addition to monitoring like Prometheus.

- Prototyping and RAD: low code tools, Figma for UI prototypes, and feature flags to test ideas in production. Match the tool with the workflow. Tools should help the model, not define it.

Final thoughts: a practical path forward

So what's the takeaway? There is no one best SDLC life cycle model for every project. The right choice depends on requirements clarity, risk, speed needs, and team maturity. I recommend starting with the simplest model that mitigates your biggest risks and iterating from there.

If you're setting up a new team, try this quick starter approach:

- Answer the five checklist questions from earlier.

- Pick one model or a lightweight hybrid to start.

- Automate builds and tests immediately.

- Run short cycles and review outcomes.

- Adjust the model based on real feedback, not theory.

What I've noticed is that teams that treat the model as a living thing do the best. They keep what works and drop what doesn't. You're allowed to adapt. In fact, you should.

Read more : Top Software Development Life Cycle Models You Haven’t Tried Yet

Helpful links & next steps

If you'd like help selecting or adapting an SDLC model for your team, let's talk. Book a meeting and we can run a short workshop to pick a practical approach that fits your constraints.

FAQs

1. What is an SDLC model in simple words?

An SDLC model is a step-by-step method that teams use to plan, build, test, and deliver software. It helps everyone stay organized and work smoothly.

2. Why do different teams use different SDLC models?

Because every project is unique. Some need fast changes, while others need strict planning. That’s why teams pick the model that fits their project style and goals.

3. Which SDLC model is best for beginners?

Most beginners find the Waterfall and Agile models easiest to understand. Waterfall is very structured, while Agile is flexible and team-friendly.

4. Are there any SDLC models that teams forget about?

Yes! Models like Spiral, V-Model, and Iterative are super helpful but often overlooked. They’re great for complex or high-risk projects.

5. How do I choose the right SDLC model for my project?

Think about your project size, timeline, budget, risks, and how often you expect changes. The “right” model is the one that matches these needs, not the trendiest one.